The Life of Merlin: A Trauma Narrative from Twelfth-Century England

By Karen Winstead

A man goes off to war. He sees his comrades, including his best friends, killed on the battlefield. He falls apart, weeping uncontrollably, refusing food for days. He returns home alive, but life has lost its meaning. His work, his pastimes, and his relationships bring him no pleasure. He can tolerate, just barely, his closest friends and family members, but crowds repel him. Music soothes him somewhat, allowing him moments of lucidity, but he is subject to violent mood swings. Once kind and generous, he now takes malicious delight in the misfortunes of others. He abandons his responsibilities, his friends, and his family for a hermit’s life, as far from the bother and business of the world as he can get. His wife, his brother-in-law, and, above all, his sister, try their best to call him back to his former life, but their efforts are counterproductive. They cannot help him because they cannot fathom the darkness that has enveloped him.

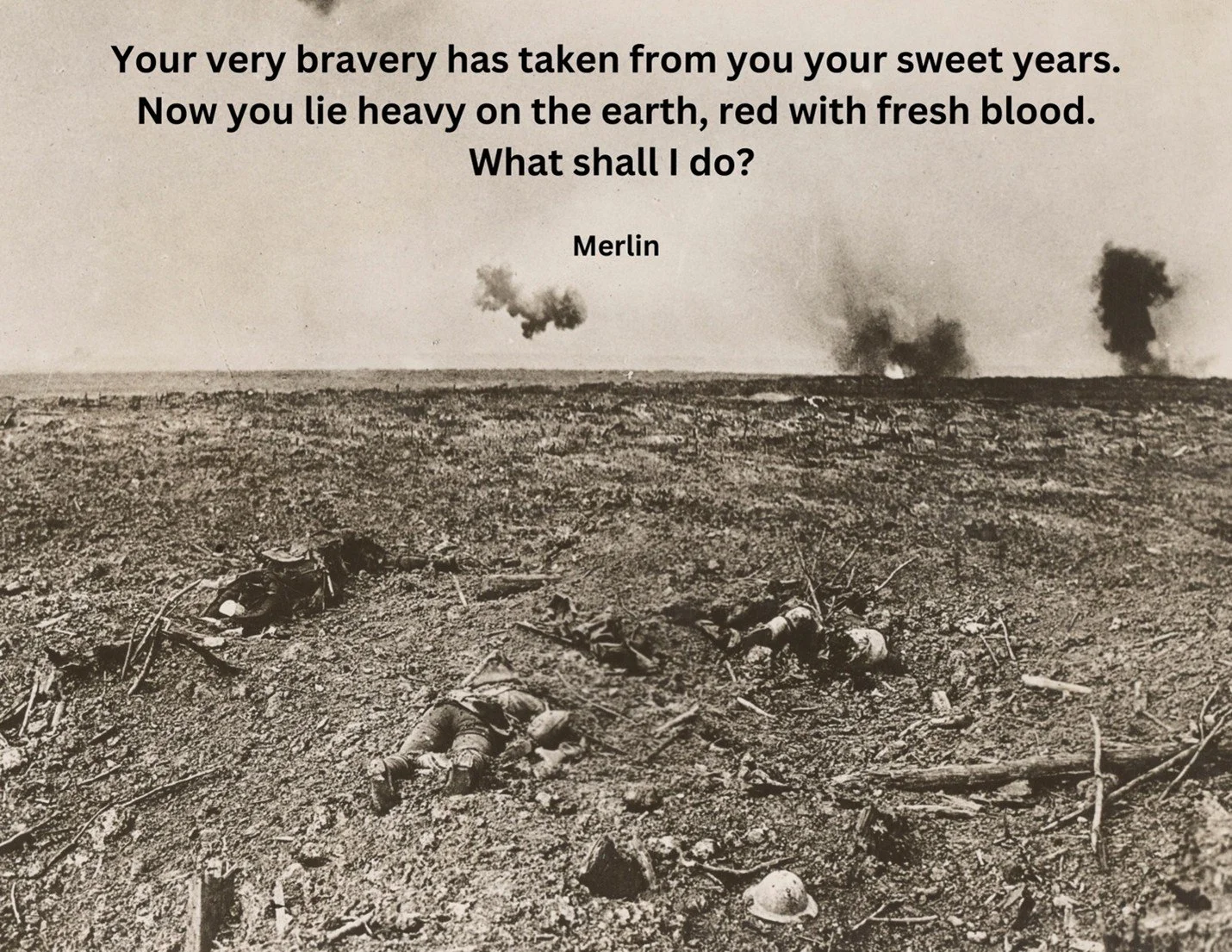

Though I might be describing a veteran of any number of modern wars suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), my subject is the inhabitant of a legendary British past as imagined by a twelfth-century historian. The battle that claimed his beloved comrades and his sanity was probably the Battle of Arfderydd, fought between the Scots and the Welsh in 573. He is Merlin, once advisor to King Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon, and now king in South Wales. His story is relayed in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Life of Merlin,[1] which is, to my knowledge, the earliest attempt to describe not only the nature of mental trauma—its causes, its symptoms, its remedy—but also its effects both on a sufferer and on that sufferer’s loved ones.

Geoffrey’s work offers a unique vantage point from which to view the mental crises that afflict so many of us today, particularly those induced by trauma. The Life of Merlin challenges us to look in nuanced ways at the distant past, appreciating at once its profound differences from our present and its equally profound connections. Below I will relay the key features of Geoffrey’s trauma narrative, then describe how that narrative has resonated both with me and with the university students I teach, many of whom have experienced trauma either personally or vicariously through friends, family members, and peers. I will conclude by gesturing towards the broader field of “trauma theory” and considering how medieval works like the Life of Merlin may alter the contours of a field that is largely focused on modernity.

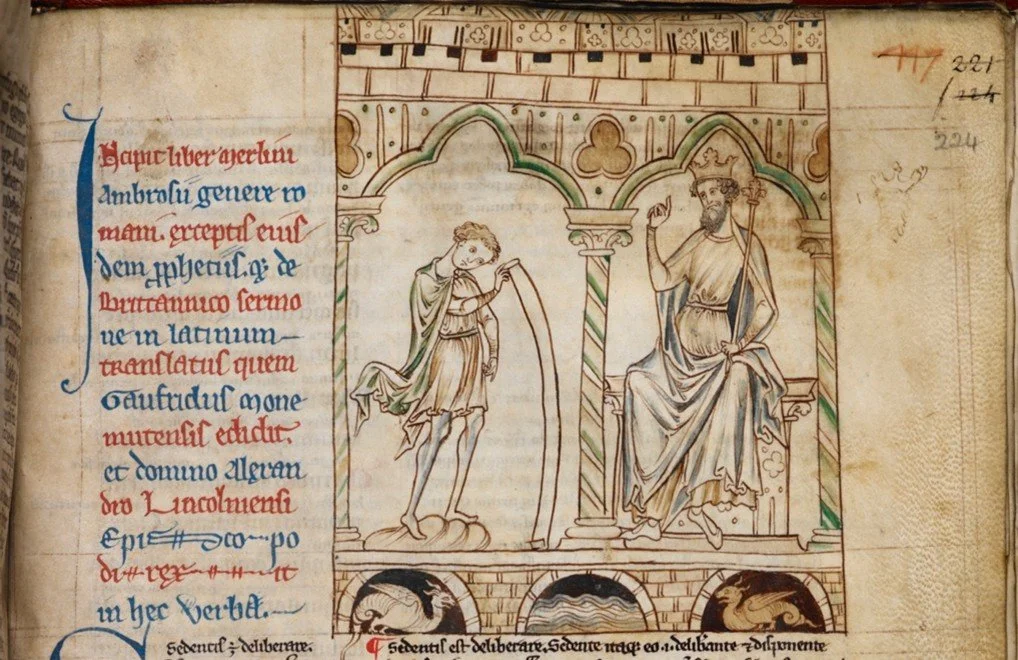

Geoffrey of Monmouth was obsessed with Merlin. Besides the Life of Merlin, he wrote the Prophecies of Merlin, and Merlin figures prominently in his magnum opus, the History of the Kings of Britain. Geoffrey reinvented and renamed a certain Myrddin, who occurs in Welsh legends and poems as a wild man, bard, and prophet. My students today tell me that they know Merlin as the wizard in modern fictions, particularly Disney’s 1963 movie The Sword in the Stone and the BBC’s TV series Merlin (2008-12). Geoffrey did not overtly associate Merlin with magic. His Merlin is an engineer, an astrologer, a prophet, and, in the Life of Merlin, a man who suffers from mental illness. His feats, as Geoffrey represents them, are always within the realm of the plausible.

Geoffrey’s history, one of the most widely circulated and influential works of the twelfth century, is a chronological narration of the reigns of British kings, enriched with vivid anecdotes. His Life of Merlin, by contrast, is in a class of its own. Though it calls itself a vita, or life story, it looks like no other medieval European life story that I have encountered. To begin with, it does not exactly deal with a person, but rather with one who has lost his personhood. It describes what Geoffrey calls the raptus, that is, the rape, or seizure, of the self. The account of Merlin’s experiences is repeatedly interrupted by digressions, flashbacks, and flash-forwards. One of its most extraordinary achievements is its documentation of a mental affliction that resembles what we know today as post-traumatic stress disorder. The Life explores the nature and cause of such an illness and its effects not only on the afflicted but on his loved ones.

Merlin’s illness is triggered by trauma, namely, the sight of friends slain in combat. His ongoing grief is no simple bereavement. To make this point, Geoffrey contrasts Merlin’s grief at the death of his friends with the later grief of his sister Ganieda at the sudden death of her husband. Ganieda is what we might call a “normal,” “healthy” mourner, one who actively seeks consolation. Though her loss devastates her and reminds her of the brevity of mortal existence, she makes a measured (and, for the time, not unusual) decision to set her affairs in order, retire from the world, and devote herself to God. Geoffrey’s readers probably knew women who had acted as Ganieda did. Merlin, however, seeks only escape. He slips away from his home, leaving his affairs in disarray and his wife, family, and subjects bewildered. Instead of subsiding, his grief grows into an illness that lasts for years, manifesting itself in mood swings, copious weeping, memory loss, and withdrawal from normal activities. These symptoms align closely with the symptoms of PTSD as they are defined by the American Psychiatric Association. He loses interest in everything that once brought him pleasure. He loses himself.

Through flashbacks, Geoffrey shows that, before his illness, Merlin was thoughtful and generous. After becoming ill, however, he is mischievous, if not downright malicious. He uses his ability as a seer to stir up trouble between his happily married sister and her husband. He titters at life’s ironies: a beggar unaware that he is sitting atop buried treasure, or a man who will not live to wear the shoes he’s just purchased. He speaks in riddles and has no care for the miseries of those he once loved, including his wife. His bouts of anger are irrational: he encourages his wife to remarry, but rages at the news of her upcoming wedding. He rants that she has abandoned him, then insists that he’s not jealous, then shows up at her home and kills her bridegroom. When imbibing the waters of a medicinal spring cures Merlin of his malady, he becomes the compassionate man he used to be. Recognizing an old friend gibbering with madness and being ridiculed by callous bystanders, he immediately offers the afflicted man a drink from the same curative waters.

Anyone familiar with mental illness today will appreciate that finding the right medicine and recovering his mental balance does not instantly solve all Merlin’s problems. Regaining his former self does not mean that he can resume his former life. Merlin is older, and both his illness and his recovery have changed him. He has lost his prophetic abilities and his taste for power. He abdicates his kingship in favor of a quasi-monastic life in the wilderness with his sister and his friends. This contemplative retirement is very different from his earlier flight from civilization; it is not a desperate escape from all human society but a freely chosen vocation that he pursues in the company of loved ones.

Besides telling of Merlin’s affliction, Geoffrey recounts the well-intentioned but counterproductive attempts of others to deal with that affliction. Merlin’s family and friends beg and badger him to come to his senses, reminding him of his responsibilities, as if his illness were his choice. They try to interest him in life with expensive gifts of clothing and hunting accoutrements. When all else fails, they bind him with chains—for his own good, they tell both him and themselves. Of course, none of these measures helps. What Merlin needs, Geoffrey shows, is the right medicine, which he fortunately obtains.

Merlin’s cure is unrealistically quick, but it is neither miraculous nor magical. Rather, it’s grounded in Geoffrey’s understanding of the natural sciences and the potentials of medicine. Merlin’s friend Taliesin talks at length about the medicine that can be harvested from gemstones, soils, and herbs. Waters from the various springs, rivers, or lakes of the world can treat a plethora of ailments: there are waters for wounds and for ailments of the eyes, waters that combat amnesia, waters that increase or decrease libido, waters that augment fertility, waters that prevent miscarriage, and waters that alleviate diseases afflicting women. That the right water might cure a mental malady such as Merlin’s would be plausible to Geoffrey and his readers.

Let me return to the veteran I conjured from the Geoffrey’s Life of Merlin in the opening paragraph of this essay. I met him in the early 2000s, when I read the Life of Merlin for the first time as part of my research on medieval genres of life writing. At the time, I was astonished to recognize in the struggles of Geoffrey’s character facets of my own struggles with clinical depression, and I resolved not only to write about him but to introduce him to my students. Fortunately, Basil Clarke’s 1973 translation of the Life of Merlin was available online, and I used it to create a reader-friendly text, supplying annotations, interpretive questions, links, and illustrations.

In teaching the Life of Merlin to scores of undergraduates and graduate students, I found that, despite Geoffrey’s convoluted and digressive narration and the strangeness of his Arthurian world, Merlin’s mental illness was as legible to students as it had been to me. The Life of Merlin is “dark and visceral in the realities it portrays,” one student reflected. Veterans identified with Merlin “as a soldier,” and those recovering from PTSD were “astonished” and “moved” by his experience. Others recognized in his experiences those they had observed in loved ones or classmates struggling from clinical depression. Students identified the yo-yoing moods, the relapses, the temporary relief obtained through music and nature, the alienation, the social anxiety, the personality changes, and much more. In the responses of Merlin’s sister and her husband, many recognized the “understandable but ignorant” exhortations that greet sufferers today: “Just don’t be sad!” “Why don’t you try to be better?” “Snap out of it!” Merlin’s suffering, one pointed out, controverts the tenacious myth that those who suffer from mental illnesses are weak-willed people who lack the discipline to pull themselves together and soldier on. Merlin, after all, is one of the super-heroes of the Arthurian universe: an intelligent, skilled prophet and leader.

Several students in my most recent Arthurian Legends course pointed out something that I had not appreciated, namely, the differences between Ganieda’s well-meant but clueless interventions and those of her husband. Ganieda did not just try to convince Merlin to like the things he used to like or to want what in her opinion he ought to want. “Though she had some missteps,” one student noted, she ultimately listened to Merlin and provided what he said he wanted, namely, a forest refuge. Perhaps most importantly, she never gave up on him, however much he rejected and hurt her: “The strongest theme I took from this reading was that love, compassion, and forgiveness are what make healing possible.”

At a time when mental illness is on the rise, especially among young people, the Life of Merlin offers an opportunity to consider, from a “safe” distance, issues that have touched us all. It is sobering to reflect on what has changed, what has not, and why. “It is all too common to experience grief all alone,” one student reflected, and it is “comforting” to know that others have shared our pain across the centuries. Merlin’s experiences remind us, too, that we have resources that weren’t available in Geoffrey’s world: better medications and, most importantly, a better understanding of mental illness. Geoffrey powerfully conveys how lonely it would be to inhabit a mental space that nobody, including yourself, understood. His chronicle of mental illness controverts the common assumption that the medieval world was simple, its denizens untroubled by our angst, their experiences irrelevant to ours.

Trauma of the sort Merlin experiences has been the subject of a burgeoning field of study since the 1990s. As Cathy Caruth, one of the founders of that field, observes, trauma “resists simple comprehension” and for that reason expresses itself “in a language that is always somehow literary: a language that defies, even as it claims, our understanding.”[2] Some trauma theorists, including Caruth, have maintained that trauma was birthed by cataclysms and upheavals of modernity, such as the Industrial Revolution, World War I, and the Holocaust (LaCapra, Kurtz),[3] but other scholars have discerned it centuries earlier (Trembinski, Clarke).[4] The Life of Merlin is a stunning example of one twelfth-century author’s attempt to express an incomprehensible reality through a disruptive, evasive, and meandering literary language, creating a story that traverses the centuries to convey realities that persist today.

Author Bio:

Karen Winstead, Professor of English at The Ohio State University, specializes in medieval literature and popular culture. Her books include Virgin Martyrs: Legends of Sainthood in Late-Medieval England, The Oxford History of Life-Writing, Volume 1: The Middle Ages, and Fifteenth-Century Lives. Her current book-in-progress deals with Thomas Malory’s Morte Darthur.

Further Reading:

Knight, Stephen. Merlin: Knowledge and Power Through the Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009.

Lawrence-Mathers, Anne. The True History of Merlin the Magician. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012.

Notes:

[1] Geoffrey of Monmouth, Life of Merlin, trans. Basil Clarke. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1973.

[2] Cathy Caruth, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016) p. 6.

[3] Dominick LaCapra, Writing History, Writing Trauma. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001; and J. Roger Kurtz, ed. Trauma and Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

[4] Donna Trembinski, “Comparing Premodern Melancholy/Mania and Modern Trauma: An Argument in Favor of Historical Experiences of Trauma,” History of Psychology 14.1 (2011): 80-99; and Catherine A. M. Clarke, “Signs and Wonders: Writing Trauma in Twelfth-Century England,” Reading Medieval Studies 35 (2009): 55-77.